“We must…consider the space between teaching and learning. Students are part of the learning process, but they do not necessarily initiate it, and teachers cannot fully instruct it.” (Symeonidis & Schwarz, 2016)

There is a space between teaching and learning where the magic lies. Not only do our students deserve teachers dedicated to learning, but teachers deserve the best learning a school can provide. Professional learning comes in many forms. Through my personal experiences I’ve found these tenants to be the most powerful in shaping my practice.

Utility – Beyond relevance, teachers need to see practical application to professional learning in their immediate environments. Our go-to utility is students that are unengaged or outliers. Yes, these are clear sign-posts that a change in instruction could support. But there are other, less obvious needs for utility. To name a few…

- Engaging in new technology without knowing where to start

- Expanding instructional practices to include more student-led work

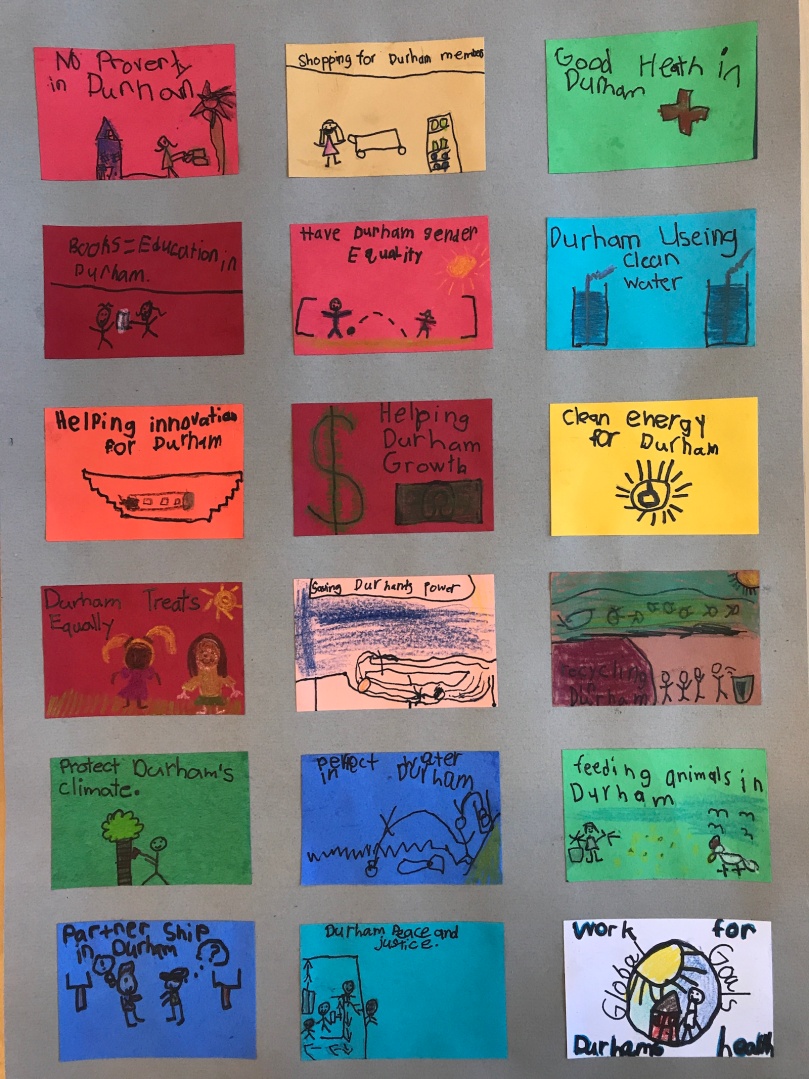

- Seeing critical needs in the world and engaging students in real-life problem solving

Instead of mandating, let’s ask teachers. “What is your most apparent need in your classroom? What is a dream that you wish you could achieve in your teaching right now?”

Multiple Modes of Learning – Just as we know lecturing and handouts don’t engage students, they also don’t engage teachers. While more PD sessions are turning to modeling instructional strategies, reflection and time to talk with colleagues, we need more real-time support. Why not try…

- Using technology to preview and engage with professional learning before a whole group session

- Creating and maintaining professional learning communities beyond the school walls

- Providing additional resources in one central location

- Making time and space for collaboration and reflection

Instead of planning sit and get sessions, let’s ask: “How do you as an adult learner engage best? In what ways could your colleagues and administration support your work?”

Different Paths – Every teacher from novice to experienced has a different skill set and a unique approach to teaching. Acknowledging and honoring these differences is not only critical, but a part of professional learning itself. As learners, teachers need space to think metacognitively about their own learning and set authentic goals. These goals should simultaneously align with the school’s mission and individual teacher needs. Shifting from stand alone professional development sessions to on-going professional learning means teachers have both responsibility for collective learning and freedom to follow their own educational interests. How schools weave these two together hinges on the success of teacher professional learning.

A Broader Purpose – If I ever started my own school, it would be a learning school. Teachers, administrators, parents, and of course students would all be learning while doing. This is the real learning. The in the moment, let’s research it to figure out how, ask an expert, or just experiment. The goal of school should no longer be to disseminate knowledge, but to grow learners. As teachers, our role has changed from keeper of knowledge to facilitator of learning. So let’s explore the space between teaching and learning and be teacher-learners together.

Symeonidis, V. & Schwarz, J. F. (2016). Phenomenon-Based Teaching and Learning through the Pedagogical Lenses of Phenomenology: The Recent Curriculum Reform in Finland. Forum Oswiatowe, 28(2), 31-47. Retrieved from http://forumoswiatowe.pl/index.phpczsopismo/article/view/458

My school, as many US schools, celebrates Martin Luther King Jr. Day in January. This year we collectively read the book We Shall Overcome by, Debbie Levy, telling the story of a song that transverses generations to inspire a better world.

My school, as many US schools, celebrates Martin Luther King Jr. Day in January. This year we collectively read the book We Shall Overcome by, Debbie Levy, telling the story of a song that transverses generations to inspire a better world. Following our school’s MKL Jr. assembly and a beautiful community sing of “We Shall Overcome” led by our

Following our school’s MKL Jr. assembly and a beautiful community sing of “We Shall Overcome” led by our  We shall overcome,

We shall overcome, To keep their goals going, next week students will engaged in a

To keep their goals going, next week students will engaged in a

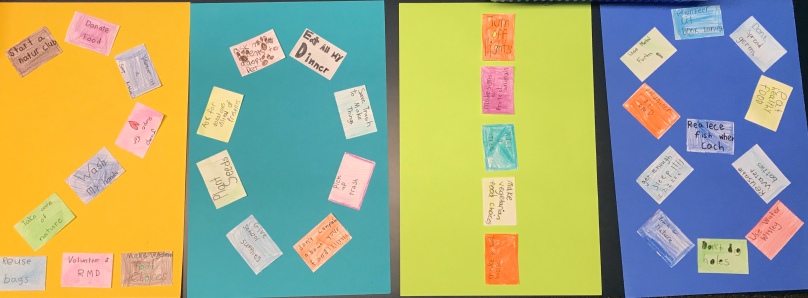

with many of us leaving the meeting feeling empowered ourselves. We researched, collaborated, created and constructed shared learning. Engaging in the process of reimagining our work with children resulted in empowered teachers. But what happens beyond the faculty meeting? How do we keep that empowerment going?

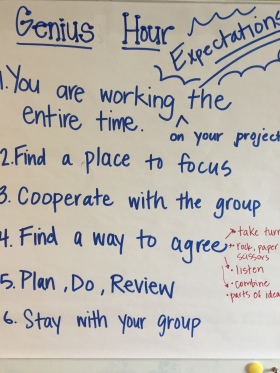

with many of us leaving the meeting feeling empowered ourselves. We researched, collaborated, created and constructed shared learning. Engaging in the process of reimagining our work with children resulted in empowered teachers. But what happens beyond the faculty meeting? How do we keep that empowerment going? ng on your project the entire time.” The rest they instilled themselves.

ng on your project the entire time.” The rest they instilled themselves.